Published: April 2020

Please note that this information will be reviewed every 3 years after publication.

This information is for you if you wish to know more about assisted vaginal birth (also known as operative vaginal birth). An assisted vaginal birth is when a healthcare professional uses specially designed instruments to help you give birth to your baby.

You may choose to read this information whilst you are pregnant to help with planning your birth.

This information may also be helpful if you are a partner, relative or friend of someone who is in this situation.

The information here aims to help you better understand your health and your options for treatment and care. Your healthcare team is there to support you in making decisions that are right for you. They can help by discussing your situation with you and answering your questions.

This information covers:

- What an assisted vaginal birth is

- Why you might need an assisted vaginal birth

- What happens during an assisted vaginal birth

- What forceps and ventouse births are

- What an assisted vaginal birth means for you and for your baby

Within this information, we may use the terms ‘woman’ and ‘women’. However, it is not only people who identify as women who may want to access this information. Your care should be personalised, inclusive and sensitive to your needs, whatever your gender identity.

A glossary of medical terms is available at A-Z of medical terms.

Key points

- In the UK, approximately 1 in 8 women have an assisted vaginal birth and this is more likely (1 in 3) for women having their first baby.

- Assisted vaginal birth includes birth helped by use of a ventouse (vacuum cup) or forceps or both. Your healthcare professional will discuss the benefits and risks of assisted vaginal birth with you.

- The majority of babies born this way are well at birth and do not have any long term problems.

- Having an assisted vaginal birth does not mean you will need one in your next pregnancy

There can be many reasons for needing help with the birth of your baby. The main ones are:

- there are concerns about your baby’s wellbeing during birth

- your labour is not progressing as would usually be expected

- you are unable to, or have been advised not to, push during birth

Overall about 1 in 8 (10-15%) births in the UK will be an assisted vaginal birth although this is much less common in women who have had a vaginal birth before. 1 in 3 women having their first baby will have an assisted vaginal birth. Your healthcare professional will discuss ways to reduce your chance of needing an assisted vaginal birth during your pregnancy.

If you have someone supporting you throughout your labour, you are less likely to need an assisted vaginal birth, particularly if the support comes from someone you know, in addition to your healthcare professional.

Assisted vaginal births are less likely if you do not have any complications in your pregnancy and plan to have your baby in a midwife-led unit. Using upright positions or lying on your side after your cervix is fully open in labour can reduce the need for an assisted vaginal birth. Having an epidural for pain relief in labour may increase the chance of you needing an assisted vaginal birth, but this is less likely with modern epidural anaesthetics.

The need for an assisted vaginal birth may be reduced by not starting to push too soon after your cervix is fully open. You may be advised to wait until you have a strong urge to push, or to try and delay pushing by 1-2 hours depending on your individual situation.

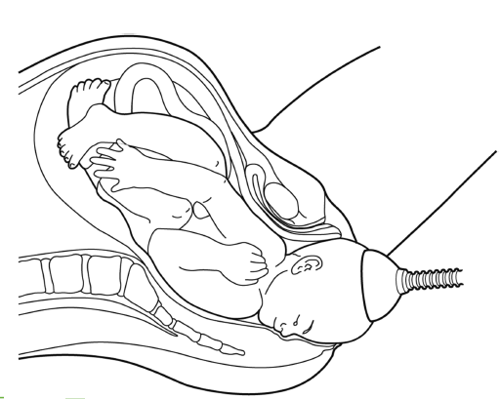

A ventouse (vacuum cup) is an instrument that uses suction to attach a plastic or metal cup on to your baby’s head. Your healthcare professional will wait until you are having a contraction and then ask you to push while they pull to help you give birth. This may happen over several contractions. Sometimes the cup can detach itself, making a “pop” sound. If this happens your healthcare professional may need to re-apply the cup to your baby's head before continuing.

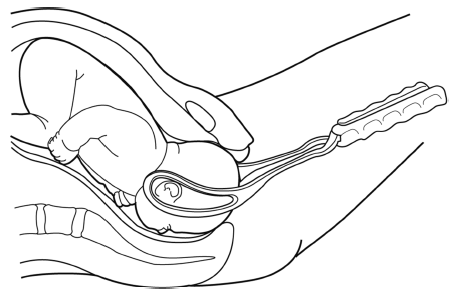

Forceps are smooth, curved metal instruments. They are made to carefully fit around your baby’s head. Your healthcare professional will wait until you have a contraction and then ask you to push while they pull with the forceps to help you give birth. This may happen over several contractions.

Ventouse and forceps are both safe and effective. Choice of instrument depends on factors including how well your epidural is working (if you have had one), the wellbeing of your baby and the position of your baby’s head. If you need an assisted vaginal birth at less than 36 weeks of pregnancy, forceps may be preferred over ventouse. This is because they involve less risk of injury to your baby’s head which is softer at this stage of pregnancy.

Your healthcare professional will recommend the method most suitable for your individual situation. If you have any concerns around the use of ventouse or forceps you should discuss this with your healthcare professional at any time during your pregnancy or labour.

If one instrument has been chosen and is not effective, your healthcare professional may then either recommend using the other instrument to help you have a vaginal birth or offer a caesarean, depending on your individual circumstances.

If neither instrument is effective in helping you give birth, your healthcare professional will recommend an emergency caesarean birth.

Forceps and ventouse will only be recommended if they are thought to be the safest way to help you give birth. The reasons for recommending an assisted vaginal birth, the choice of instrument and the procedure will be discussed with you at the time. If you are in labour and choose not to have an assisted vaginal birth, the alternatives are to wait for your baby to be born without assistance or to have an emergency caesarean. Your healthcare professional will discuss your options depending on your individual circumstances.

A caesarean in the late stage of labour is a more complex operation than a planned caesarean and in some circumstances may increase the risk of harm to both you and your baby.

Decision making in labour can be difficult which is why it is important to explore any concerns you may have with your healthcare professional before you go into labour.

If you are certain you would not want an assisted vaginal birth, one option is to choose a planned caesarean birth before you go into labour. If you are considering a planned caesarean you should discuss this with your healthcare professional during your pregnancy. For more information, refer to the RCOG patient information on caesarean birth.

With your consent, your healthcare professional will examine your abdomen and perform an internal examination to confirm that an assisted vaginal birth is safe for you and your baby. You will usually be asked to sit with your legs supported and your bladder will be emptied by passing a small tube (catheter) into it.

Pain relief for the birth may be either a local anaesthetic injection inside the vagina or a regional anaesthetic injection into your back (an epidural or a spinal). For more information about pain relief during labour see the Labour Pains website (labourpains.org) from the Obstetric Anaesthetists’ Association.

You are more likely to need to have a cut (episiotomy) to enlarge your vaginal opening and allow your baby to be born.

A healthcare professional who specialises in the care of newborn babies may be there when you give birth in case your baby needs some extra help after birth. If your baby is well you may choose to have immediate skin to skin contact and/or delayed cord clamping.

After your baby is born you will be given some antibiotics through a drip to reduce the chance of you developing an infection.

If your healthcare professional expects your assisted vaginal birth to be straightforward, they will recommend that you give birth in the same room where you have been in labour. If they think that the assisted vaginal birth may be more complicated or that there is a chance that it might not work, you will be advised to give birth in the operating theatre. This is so that you can have an immediate caesarean if necessary.

Assisted vaginal birth is less likely to be successful if:

- you are overweight with a body mass index (BMI) over 30;

- you are less than 161cm in height

- your baby is estimated to be more than 4kg in weight

- your baby is lying with its back to your back at the end of your labour

- your baby’s head is not low down in the birth canal at the end of your labour

You may need to stay in hospital for longer than originally expected after the birth of your baby.

Bleeding

It is normal to have vaginal bleeding after you have given birth. Straight after an assisted vaginal birth, heavier bleeding is more common. The bleeding in the days afterwards should be similar to an unassisted vaginal birth.

Vaginal tears/ episiotomy

Birth with ventouse and with forceps does mean a higher chance of you needing to have an episiotomy or having a vaginal tear. If you have either a vaginal tear or an episiotomy, this will be repaired straight after birth with dissolvable stitches. For further information see www.rcog.org.uk/tears.

A third- or fourth-degree tear (a tear which involves the muscle and/or the wall of the anus or rectum) affects 3 in 100 women (3%) who have a vaginal birth. It is more common following a ventouse birth, affecting up to 4 in 100 women (4%) and following a forceps birth, affecting between 8 and 12 women in every 100 (8–12%).

Further information

Further information can be found on the RCOG information hub on perineal tears and in the RCOG Patient Information Care of a third- or fourth-degree tear that occured during childbirth (OASI).

Sources and acknowledgements

This information has been developed by the RCOG Patient Information Committee. It is based on the RCOG Green-top Guideline Assisted Vaginal Birth (published alongside this information in April 2020). The guideline contains a full list of the sources of evidence we have used.

It is also based on the RCOG Consent Advice 11 on Operative Vaginal Birth.

Before publication this information was reviewed by the public, by the RCOG Women’s Network and by the RCOG Women’s Voices Involvement Panel.