Published: March 2013

Please note that this information will be reviewed every 3 years after publication.

Updated: May 2022

This information is for you if you have pelvic organ prolapse and want to know more about it.

It may also be helpful if you are a partner, relative or friend of someone who is in this situation.

The information here aims to help you better understand your health and your options for treatment and care. Your healthcare team is there to support you in making decisions that are right for you. They can help by discussing your situation with you and answering your questions.

Within this information we may use the terms ‘woman’ and ‘women’. However, it is not only people who identify as women who may want to access this leaflet. Your care should be personalised, inclusive and sensitive to your needs whatever your gender identity.

A glossary of medical terms is available at A-Z of medical terms.

Key points

- Pelvic organ prolapse is common, affecting 1 in 10 women over the age of 50 years. Mild prolapse often causes no symptoms and treatment is not always necessary.

- Prolapse can affect quality of life by causing discomfort. You may also experience a feeling of heaviness or a dragging sensation in the pelvis which may get worse as the day progresses. It can also cause bladder and bowel symptoms, and having sex may feel different.

- Prolapse symptoms can be reduced with lifestyle changes, including stopping smoking, weight loss, avoiding constipation where possible and heavy lifting.

- Treatment choices for prolapse include physiotherapy, support pessaries or surgery.

- Your choice of treatment will depend on how the prolapse affects your quality of life. Not everyone with prolapse needs surgery or any other form of treatment.

- Treatment for prolapse aims to support the pelvic organs and helps to ease your symptoms. It does not always cure the problem completely and prolapse may return.

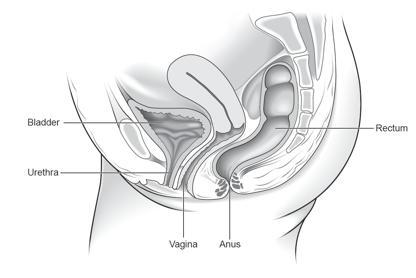

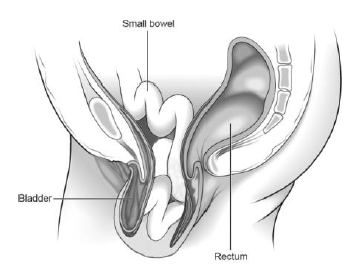

The organs within a woman’s pelvis (uterus, bladder and rectum) are normally held in place by ligaments and muscles known as the pelvic floor. If these support structures are weakened by overstretching, the pelvic organs can bulge (prolapse) from their natural position into the vagina. When this happens it is known as pelvic organ prolapse. Sometimes a prolapse may be large enough to protrude outside the vagina.

Normal female pelvis

There are different types of prolapse depending on which pelvic organ is bulging into the vagina. It is common to have more than one type of prolapse at the same time. The prolapse can be of various degrees (grades or stages) depending on how far down the prolapse is coming. It is important to distinguish between the different types and degree of pelvic organ prolapse as their symptoms and treatment may differ.

The most common types of pelvic organ prolapse are:

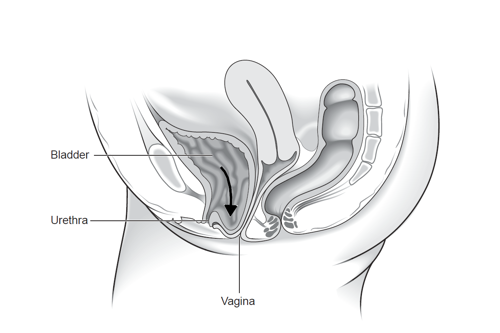

Anterior vaginal wall prolapse: when the bladder and/or urethra bulges into the front wall of the vagina. This is also called a cystocele or cystourethrocele.

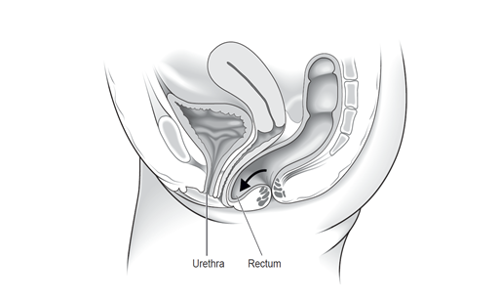

Posterior vaginal wall prolapse: when the rectum (lower part of the large bowel) bulges into the back wall of the vagina, also called a rectocele. The small bowel may also bulge into the back wall of the vagina, this is called an enterocele.

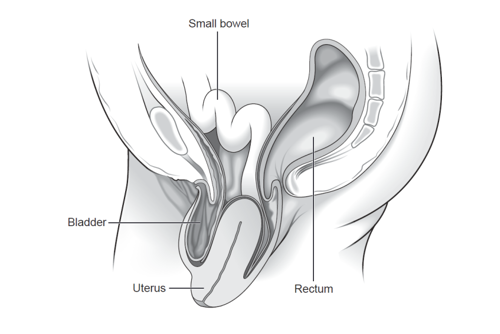

Uterine prolapse: when the uterus drops or sags down into the vagina. Eventually, the uterus may protrude outside the body and if the whole uterus is completely outside the vagina this is called a procidentia.

Vault prolapse: when the top of the vagina (or vault) bulges down. This can happen if you have had a hysterectomy and may develop in up to 1 in 10 women.

It is difficult to know exactly how many women are affected by prolapse since many do not see their doctor for it. However, it appears to be very common, especially in the older age group. In women over the age of 50 years, 1 in 10 will have some symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse.

Pelvic organ prolapse can happen when the pelvic floor weakens. A weak pelvic floor can be due to the following:

- pregnancy and childbirth

- ageing – prolapse is more common as you get older, particularly after your menopause

- being overweight

- persistent constipation, coughing or heavy lifting

- a natural tendency to develop prolapse

Often it is a combination of these factors that result in you having a prolapse.

Your symptoms will depend on the type and degree of your prolapse. The following is a list of possible symptoms:

- You may not have any symptoms at all.

- You may feel a bulge or a dragging sensation in the vagina. You may also have backache, heaviness or discomfort inside your vagina. These symptoms are often worse if you have been standing for a long time and may improve on lying down.

- You may be able to feel or see a bulge in your vagina.

- You may need to pass urine more frequently and urgently. Also, you may have difficulty in passing urine or a sensation that your bladder is not emptying properly.

- You may leak urine when coughing, laughing; lifting heavy objects or you may have frequent bladder infections (cystitis).

- You may notice constipation or incomplete bowel emptying. You may sometimes need to press on the bulge with your fingers to help open your bowels.

- You may be anxious about sex, find it uncomfortable or notice a lack of sensation during intercourse.

Some of the above symptoms may not be directly related to your prolapse.

Prolapse is diagnosed by performing an internal examination. Your healthcare professional will examine your vagina using a speculum to see exactly which organ(s) is bulging. You may be asked to lie on your side with your knees drawn up towards your chest for this examination or you may be examined standing up. Prolapse is staged from 1 to 4 depending on the degree of the prolapse. Women with Stage 1 usually have mild or no symptoms and rarely need treatment.

You will be offered a urine test to check for infection. If you have bladder symptoms, like leaking urine or being unable to empty your bladder fully, your doctor may advise a bladder scan and may check how your bladder is working using tests known as urodynamics.

No. You may choose not to have any treatment or be advised to take a ‘wait and see’ approach. Prolapse is not life threatening, but it may affect the quality of your life.

Your symptoms may stay the same, get worse or sometimes even improve over time.

Your options for treatment will depend on the type and degree of prolapse you have and your individual circumstances, such as age, general health, whether you are sexually active and whether you have completed your family. Your options include:

Lifestyle changes:

- losing weight if you are overweight

- managing a long-standing cough if you have one

- stopping smoking

- avoiding constipation

- avoiding heavy lifting

- avoiding physical activity that impacts on the pelvic floor, like running or trampolining.

Pelvic floor muscle exercises: to strengthen your pelvic floor muscles you may be referred to a specialist women’s health physiotherapist for a course of physiotherapy treatment (3–6 months). Pelvic floor exercises may not get rid of your prolapse but are likely to improve your symptoms. Even if you are considering surgical treatment, it is advisable to continue with pelvic floor muscle training to improve your overall chances of successful treatment.

Even if you do not currently have any symptoms, you may wish to consider pelvic floor exercises and lifestyle changes to prevent your prolapse from getting worse.

Vaginal hormone treatment (estrogen): if you have gone through the menopause, your doctor may recommend vaginal estrogen treatment in the form of tablets, cream or a ring that is inserted into your vagina. Estrogen treatment can help to reduce the discomfort you may experience from having a prolapse.

Vaginal support pessary: a pessary is a plastic or silicone device that fits into your vagina to help support the pelvic organs. This can be an effective way of helping your symptoms.

A pessary is suitable for most people. You may choose this option if you are thinking about having children in the future, you do not wish to have surgery or you have a medical condition that makes surgery riskier. You may also choose to use a pessary while you are waiting to have surgery.

There are different types and sizes of pessaries, and your doctor or specialist nurse will advise which one will suit you best. Ring pessaries are most commonly used.

Identifying the correct pessary may take more than one attempt as there are many different sizes and shapes. Pessaries should be changed or removed, cleaned and reinserted every 4–6 months. This can be done by your doctor, nurse or you may be able to do this yourself.

Pessaries do not usually cause any problems but can sometimes cause infection, discharge, bleeding or ulceration. Very rarely, the pessary may get stuck. If you have any concerns, you should see your doctor. It is possible to have sex with certain types of pessaries in place, but you and your partner may occasionally be aware of it. Some women may choose to remove it before having sex and reinsert it afterwards.

Surgery:

Whether you choose to have surgery will depend on how severe your symptoms are and how your prolapse affects your daily life. You may want to consider surgery if other options have not helped.

There are risks with any surgery. These risks are higher if you are overweight, smoke or have medical problems. Your doctor will discuss this with you so you can decide whether you wish to go ahead with your surgery.

If you plan to have children, you may be advised to delay surgery until your family is complete. This is because another pregnancy and birth may increase the chance of your prolapse happening again.

There are many different types of surgery for prolapse. Your gynaecologist can advise which surgery is best for you. This will depend on your type of prolapse and symptoms, as well as your age, general health, your wish to have sexual intercourse and whether or not you have completed your family. If there is more than one choice, your gynaecologist will explain the pros and cons of each.

Surgery for prolapse is usually performed through the vagina but may involve keyhole surgery or a cut in your abdomen (tummy). You may occasionally be referred to a specialist unit.

Possible types of surgery include:

- Pelvic floor repair to treat the vaginal bulge. This is where the walls of your vagina are repaired to support the pelvic organs. This is usually done through your vagina.

- Vaginal hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) is sometimes performed for uterine prolapse. Your gynaecologist might recommend that this be performed at the same time as a pelvic floor repair. This is done through your vagina without a cut on your abdomen. Occasionally, you may need a cut on your abdomen if you have excessive bleeding or an enlarged womb.

- Sacrocolpopexy uses a mesh (synthetic net-like fabric or natural tissue) to attach the top of your vagina (vault) to the bottom of your spine (sacrum). This may be done by keyhole surgery or a cut on your abdomen. Further information about mesh is available below.

- Sacrospinous fixation uses sutures (stitches) to secure the top of your vagina to a strong ligament in the pelvis. This is done through a cut in the vagina.

- Sacrohysteropexy uses a mesh to attach your womb to the bottom of your spine. This may be done by keyhole surgery or a cut on your abdomen. Further information about mesh is available below.

- Colpocleisis involves partial or complete closing of your vagina. It has lower risks than other types of surgery for prolapse. This may be offered if you are in poor medical health or if you have had several operations previously that have been unsuccessful. Vaginal intercourse is not possible after this operation.

Surgery to treat urinary incontinence may occasionally be carried out at the same time as surgery for prolapse.

For further information on types of surgery, see the NICE Patient decision aid on Surgery for vaginal vault prolapse and NICE Patient decision aid on Surgery for uterine prolapse.

The British Society of Urogynaecology (BSUG) have published information on Operations to treat Prolapse of the Uterus (Womb Prolapse).

Further information on mesh

Surgery involving the use of synthetic mesh (made of plastic) has more complications. Some women may experience long term pain after mesh insertion. The mesh can wear through (erode) the vagina in up to 1 in 10 women. Mesh erosion can cause pain, vaginal discharge, bleeding or narrowing of the vagina, and pain with sex. It is also possible for the mesh to erode into your bladder or bowel, but this is less common. It may not be possible to remove the mesh or fully relieve problems arising in the future from mesh.

If you are considering a procedure using mesh, you should have a detailed discussion with an expert healthcare professional (Urogynaecologist) about the benefits and risks of the surgery for you. If you decide to go ahead with a procedure using mesh, the operation should only be performed by an accredited specialist with expertise in this technique. Since July 2018, national restrictions have been in place for procedures for prolapse involving mesh, which include accreditation of specialist centres and surgeons, and a national database of all mesh procedures (insertion and removal).

If you have had vaginal mesh inserted and think you are experiencing complications, or you want to find out about the risks involved, speak to your GP. You can also report a problem with a medicine or medical device through the government’s website. https://www.gov.uk/report-problem-medicine-medical-device.

Depending on which operation you are having, your surgery may be done with you asleep (general anaesthesia), after being numbed from the waist down (spinal anaesthesia), with sedation or with local anaesthesia. Your doctor will be able to discuss these options with you before the operation.

You may feel more comfortable and your bladder or bowel may work better. The benefits of some types of surgery last longer than others.

The risks depend on the type of surgery you have and your general health.

Common risks after surgery include:

- bleeding, which may need a blood transfusion or return to theatre

- infection, requiring antibiotics

- pain during intercourse

- return of the prolapse after surgery.

Some women find their bladder problems are no better and others develop new bladder problems after surgery, such as difficulty in passing urine or leaking urine.

Uncommon risks include:

- damage to your bladder or bowel

- development of a clot in the legs or lungs

- pelvic abscess.

Complications of surgery for vault prolapse

There are two main types of surgery for vault prolapse, sacrocolpopexy (with mesh) and sacrospinous fixation (with sutures). In addition to the above risks, there are specific differences relating to these two types of surgery.

The risk of prolapse returning, pain during sex and urinary problems are less common after sacrocolpopexy, however recovery is quicker, and there may be fewer problems with constipation after sacrospinous fixation. Additionally, sacrospinous fixation avoids the possibilities of mesh-related complications.

Pain in the buttock may develop in 1 in 5 women after sacrospinous fixation, which usually settles within 3 months.

The length of time you need to spend in hospital after surgery will vary depending on the type of surgery and how quickly you recover. You should avoid heavy lifting after surgery and avoid sexual intercourse for 6–8 weeks.

For further information on recovering after your operation, please see the RCOG patient information on recovering well from gynaecological procedures: www.rcog.org.uk/recoveringwell

No surgery can be guaranteed to permanently cure your prolapse, but most offer a good chance of improving your symptoms.

Approximately 25–30 in 100 women having surgery for prolapse will develop another prolapse in the future. There is a higher chance of the prolapse returning if you are overweight, constipated, have a long-standing cough or undertake heavy physical activities. Prolapse may occur in another part of the vagina and you may need further treatment.

If you are asked to make a choice, you may have lots of questions that you want to ask. You may also want to talk over your options with your family or friends. It can help to write a list of the questions you want answered and take it to your appointment.

Ask 3 Questions

To begin with, try to make sure you get the answers to 3 key questions, if you are asked to make a choice about your healthcare:

- What are my options?

- What are the pros and cons of each option for me?

- How do I get support to help me make a decision that is right for me?

*Ask 3 Questions is based on Shepherd et al. Three questions that patients can ask to improve the quality of information physicians give about treatment options: A cross-over trial. Patient Education and Counselling, 2011;84:379-85

First Do No Harm - The Cumberlege Report

On 8 July 2020 the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review, chaired by Baroness Julia Cumberlege, was published. This addressed reports from patients of harm from drugs and medical devices, including vaginal mesh.

The RCOG and BSUG thank women for their courage in coming forward and sharing their painful and distressing accounts. The RCOG and BSUG have pledged to act on the recommendations within the report, to support trainees and specialists to learn from the report, and to provide the highest standard of care together with information to support women in their decision making for treatment for pelvic organ prolapse. Together with specialist centres, the RCOG is working to provide women who have had complications from mesh surgery with appropriate and safe treatment.

About intimate examinations

The nature of obstetrics and gynaecological care means that intimate examinations are often necessary. We understand that for some people, particularly those who may have anxiety or who have experienced trauma, physical abuse or sexual abuse, such examinations can be very difficult. If you feel uncomfortable, anxious or distressed at any time before, during or after an examination, please let your healthcare professional know. If you find this difficult to talk about, you may communicate your feelings in writing. Your healthcare professionals are there to help and they can offer alternative options and support for you. Remember that you can always ask them to stop at any time and that you are entitled to ask for a chaperone to be present. You can also bring a friend or relative if you wish.

Further information

British Society of Urogynaecology (BSUG) information

BSUG information: Operations to treat Prolapse of the Uterus (Womb Prolapse)

NICE guideline on Urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women: management

NICE Patient decision aid on Surgery for vaginal vault prolapse patient decision

NICE Patient decision aid on Surgery for uterine prolapse

Women’s Health Concern information on prolapse

NHS information on pelvic floor exercises

NHS Squeezy app for pelvic floor excises

Pelvic Obstetric and Gynaecological Physiotherapy (POGP)

First Do No Harm – report from the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review

Report a problem with a medicine or medical device

A full list of useful organisations (including the above) is available on the RCOG website at Other sources of help.

Sources and acknowledgements

This information has been developed by the RCOG Patient Information Committee. It is based on the RCOG/BSUG Joint Green-top Guideline no. 46 Post-Hysterectomy Vaginal Vault Prolapse published in July 2015. It is also based on the NICE guideline on Urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women: management. The guidelines contains a full list of the sources of evidence we have used.