Updated: October 2024

About this information

Being told that your baby has died before birth is devastating for you, your partner and those close to you. This information is for you if your baby has died before birth but after 24 weeks of your pregnancy. This is called a stillbirth. You may also find some of the information useful if your baby has died earlier than 24 weeks (when it is called a miscarriage). It may also be helpful if you are a partner, relative or friend of someone in either situation.

You will be given lots of support and information by your healthcare professionals. This information is to help explain the care you will receive during and after the birth of your baby, and care in any future pregnancies. If at any time you feel uncertain about anything, the healthcare team looking after you will be there to help.

Within this information we may use the terms ‘woman’ and ‘women’. However, it is not only people who identify as women who may want to access this information. Your care should be personalised, inclusive and sensitive to your needs whatever your gender identity.

This leaflet does not discuss the longer-term emotional support you may need. Sources of further support and information are listed at the end of this information.

The RCOG also provides a glossary of medical terms in the A-Z of Medical Terms.

Key points

- Emotional support is essential when your baby has died – your healthcare team will support you, and additional support is available from a number of other organisations.

- It is up to you to decide when and how to birth your baby. Your healthcare team will give you the information you need to help you decide. Vaginal birth is usually recommended, but the decision is yours.

- You will be supported after the birth to spend time with your baby if you wish, together with opportunities for memory making and help with funeral arrangements.

- You will be offered different investigations to try to find out why this has happened. Unfortunately a cause may not always be found.

- You will be offered follow up with your healthcare professional to review the results of investigations and to make a plan of care for any future pregnancies.

A baby dying before birth happens in one in every 250 pregnancies. The question that most parents wish to have answered is ‘why did my baby die?’. Unfortunately, it is not always possible to give an answer. A cause can be found for around two out of three stillbirths, when investigations have been performed.

The most common cause is that something has prevented the placenta from providing everything your baby needs to survive. There are many possible reasons for this, including infections, complications from diabetes, early separation of your placenta (placental abruption) and pre-eclampsia (high blood pressure and protein in your urine).

Sometimes your baby may have an underlying genetic or physical condition that has caused them to die. Rarely, something can happen during labour that can lead to your baby’s death.

Stillbirth is confirmed by an ultrasound scan. The scan will show that your baby’s heart has stopped beating. This will usually be confirmed by a second person scanning, either at the same time or later. If you wish, you can ask for another scan at any time.

Sometimes, after it has been confirmed that your baby has died, you may still feel as if your baby is moving. This is caused by the shifting movements of your baby within the amniotic fluid in your uterus (womb).

Your healthcare professionals will talk to you and your birth partner about the death of your baby. They will also check to make sure that you are physically well (for example making sure that you have no signs of infection and that your blood pressure is normal).

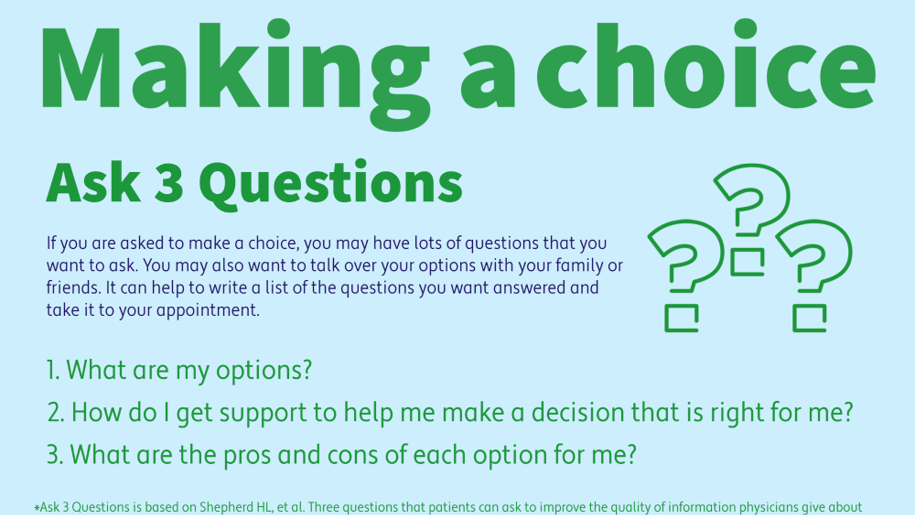

They will explain your choices for birth, and the various tests that will be offered. You will be given information, support, privacy and plenty of time to help you make your decisions. You will be encouraged to have your partner or anyone you choose to be with you.

Your healthcare team will discuss with you the different options of when, where and how to have your baby. The advice will depend on your general health, your pregnancy and any previous birth experiences, together with your personal wishes. Your choice of where to give birth will depend on your preference as well as your medical condition.

You will be looked after by a midwife throughout and, where possible, you will be cared for in a private area that has facilities for your partner or another companion to stay with you.

How will I give birth to my baby?

- You may choose to have your baby vaginally or to have a caesarean birth. Vaginal birth is usually recommended. This is because, compared to a caesarean birth, there are fewer risks to you.

- you will be able to go home more quickly

- your recovery is likely to be quicker and more straightforward

- future pregnancies are less likely to have complications.

Some women find that labouring to give birth to a stillborn baby adds to their distress, but for others it is a positive experience. Your healthcare professional will discuss your choices with you and your wishes will be respected. You will be offered pain relief to make you comfortable for your labour and birth.

Inducing labour

You may choose to have your labour started (known as induction of labour) as soon as possible after confirmation of your baby’s death, or you may prefer to go home for a short while before you give birth. There are different ways of starting labour and your healthcare professional will discuss with you the benefits and risks of each method, taking into account your personal circumstances.

A tablet will often be given to you up to 48 hours before labour is started, to help prepare your body for labour. The time it takes for your labour to start can vary from person to person.

Waiting for the natural onset of labour

You may choose to wait at home for labour to start naturally. If your waters have not broken and you are well physically, you are unlikely to come to any harm if you delay labour for a short period of time. Most women will go into labour naturally within 3 weeks of their baby dying. If you decide to wait for more than 48 hours, you will be advised to have a check-up at the hospital twice a week as a small number of women can become unwell during this time.

It is important to consider that delaying the birth of your baby will affect their appearance at birth. In addition, tests that you agree to being carried out on your baby may give less information about why your baby died.

Your healthcare team will give you a 24-hour contact number to ring if you have any queries or concerns while waiting for labour to start. You should contact your maternity unit if:

- your waters break or you think labour is starting

- you have vaginal bleeding

- you have a change in your vaginal discharge

- you feel unwell in any way.

You will be advised against delaying labour if you have pre-eclampsia, blood clotting problems, an infection, or any other condition that may affect your health if you delay birth.

What if I have had a caesarean birth before?

If you have had one previous caesarean birth, it is usually safe to have labour induced although it is not completely without risk. If you have had more than one previous caesarean birth, the risks of induction and labour increase and a caesarean birth may be advised. See RCOG information on Birth options after previous caesarean section: https://www.rcog.org.uk/for-the-public/browse-all-patient-information-leaflets/birth-after-previous-caesarean-patient-information-leaflet/.

You will be supported by the healthcare professionals looking after you. You and your partner (and sometimes other members of your family, with your permission) may wish to see and/or hold your baby immediately after birth. You may like to wait to see your baby until a little later after birth. You may decide not to see your baby at all.

If you wish to see and hold your baby, then you will have the opportunity to spend as much time as you want with them. You will be able to name your baby, and dress them in their own clothes, if you wish.

Mementoes such as photographs, hand and footprints and locks of hair, if possible, can be taken, and these are often valued by parents. These will only be done with your permission. If you do not wish to take these home with you straight away, they can be kept securely in your hospital records. You can then have them at a later date if you want.

Sometimes it can be difficult to be completely certain whether your baby is a boy or a girl, especially earlier in pregnancy, and when there is delay between your baby’s death and their birth. In this situation it may be possible to do a rapid genetic test to try to confirm the baby’s sex.

A member of the bereavement team will talk to you and your partner about the funeral choices for your baby, and about registering the stillbirth. Any religious and cultural preferences you have will be respected, and spiritual support will be available.

Grief is an individual experience, and will vary in how it affects you, your partner and those close to you. For some people, grief following the death of a baby can be severe and last a long time. Options for support and bereavement counselling should be offered to you and your partner. Your GP will be informed, and you will be given information on the different support available to you.

You can usually go home when you wish, although if you have been unwell you may be advised to stay in the maternity unit for a little longer. Some women want to go home as soon as possible, whereas others prefer to stay for a while. In some circumstances it may be possible for your baby to come home with you – the bereavement team can discuss this with you in detail if you wish to consider this.

After the birth of your baby you may experience the sensation of breast milk coming into your breasts. Your healthcare professional will discuss options with you, including preventing your milk with medication, allowing milk to come and waiting for it to stop naturally, or donating your milk, for example, to the neonatal unit. While discomfort may be reduced with measures such as the use of ice packs, breast support and pain relief, you may still experience pain from your breasts becoming full with milk.

As with any birth, you will be offered home visits by your midwife who will check your recovery and will also be able to provide support and talk through any questions you may have.

You will have some bleeding and pain which should settle down within several weeks. Problems are uncommon after birth but you should contact your GP or hospital if:

- your bleeding gets heavier

- you have pain in your abdomen that doesn’t settle

- you have a smelly vaginal discharge

- you feel unwell or shivery

- you have pain, swelling or soreness in your legs

- you have shortness of breath or chest pain, or cough up blood.

You will be offered investigations for you and your baby that may help to find out why your baby has died. A cause is found in up to two-thirds of stillbirths. Understanding why your baby died could be helpful to you, and can help with planning your care in any future pregnancy. Unfortunately, despite investigations, some deaths cannot be explained. Some investigations may cause a delay in funeral arrangements.

You and your partner will be given time to think about which investigations you would like to have done and you will be supported in any choices you make. You will need to sign a consent form for some of the investigations. You will be offered an appointment at a later date to discuss the results.

Investigations you may be offered include:

- A test of your baby’s chromosomes that will involve a sample of the placenta, umbilical cord or a skin sample from your baby. This test is important because approximately one in 17 of stillborn babies have a problem with their chromosomes. Sometimes more detailed genetic tests are recommended.

- A post-mortem examination of your baby, which can be as limited or detailed as you wish. This examination can provide very important information about why your baby has died and will increase the likelihood that a cause can be identified. You will be given further detailed written information about this and time to discuss your choices with a healthcare professional. It will be your decision for your baby to have a post-mortem examination and you will need to give your consent and sign a form before this test can be done. You can find further information on post-mortem examinations on the Sands post-mortem examination webpage.

- A detailed examination of your placenta.

- Blood tests to look for a number of conditions, including:

- pregnancy specific problems such as pre-eclampsia and obstetric cholestasis

- diabetes

- maternal infections

- conditions that can make your blood more likely to clot (thrombophilia or antiphospolipid syndrome).

- If infection is suspected then more detailed tests including swabs from your vagina, cervix, placenta, and from your baby may be recommended.

A follow-up appointment with your obstetrician will be arranged to discuss the results of the tests. The date of your appointment will be confirmed once all test results are available. This may take several months if your baby has had a post-mortem. If you would find it distressing to return to the maternity unit where your baby was born, tell your healthcare professionals so that an alternative can be arranged.

You may find it helpful to write down, beforehand, any questions that you wish to discuss at your follow-up appointment. Your healthcare professional will discuss with you and your partner how best to prepare for another pregnancy, and the care that you will be offered if you decide to have another baby.

Your healthcare team will review your baby’s death, and you will have the chance to contribute to this and receive information about the findings of the review if you wish.

Further grief counselling and psychological help can be accessed through your midwife / GP / Health Visitor if you want this.

If you choose to have another baby, you will be offered specialist care, including extra antenatal visits and scans in addition to your usual midwife appointments. You will understandably be anxious. You will be given additional support by the healthcare professionals looking after you throughout your pregnancy, who will be aware of your previous loss.

You will have an individualised plan of care for your pregnancy, which will depend on the results of any tests you have had and whether a cause has been found for the death of your baby. Your healthcare professional may offer you the option of induction of labour or planned caesarean, usually by 39 weeks of pregnancy, after taking into account your wishes and any relevant medical factors.

Further information and support

- SANDS (Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Charity): offers emotional support and practical help to anyone affected by the death of a baby before, during or shortly after birth. As well as supporting mothers and partners, Sands can help other members of the family, especially grandparents and other children, as well as friends.

Helpline: 08081643332 (available from 10am to 3pm Monday to Friday and 6pm to 9pm Tuesday and Thursday evenings)

Email: helpline@sands.org.uk - Tommys: Online resources and bereavement-trained midwives available Monday to Friday 9am to 5pm.

Telephone: 0800 0147 800 - National Bereavement Care Pathway: This pathway was established to improve the quality and consistentsy of bereavement care provided by healthcare professionals for parents, after the death of their baby.

- National Perinatal Mortality Review Tool: This information explains how the care of the mother and baby will be reviewed, when a baby dies before birth.

- National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit: Information on National Perinatal Mortality Review Tool.

- Twins Trust: Bereavement Support Group: to support all parents of twins, triplets or more who have died whether it was during or after pregnancy.

Sources and acknowledgements

This information has been developed by the RCOG Patient Information Committee. It is based on the RCOG guideline Late Intrauterine Fetal Death and Stillbirth (Published October 2024). The guideline contains a full list of the sources of evidence we have used