Published: July 2015

Please note that this information will be reviewed every 3 years.

This information is for you if you want to know more about umbilical cord prolapse.

It may also be helpful if you are a partner, relative or friend of someone who has been in this situation.

The information here aims to help you better understand your health and your options for treatment and care. Your healthcare team is there to support you in making decisions that are right for you. They can help by discussing your situation with you and answering your questions.

This information tells you:

- Why umbilical cord prolapse is an emergency

- Whether cord prolapse can be predicted or prevented

- When a cord prolapse is more likely happen

- Signs of a cord prolapse

- What you should do if you think you have had a cord prolapse

- Treatment options

- What a cord prolapse could mean for your baby

Within this information, we may use the terms ‘woman’ and ‘women’. However, it is not only people who identify as women who may want to access this information. Your care should be personalised, inclusive and sensitive to your needs, whatever your gender identity.

A glossary of medical terms is available at A-Z of medical terms.

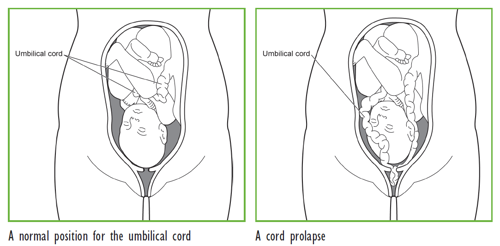

The umbilical cord connects the baby from its umbilicus (tummy button) to the placenta inside the womb (uterus). The cord contains blood vessels that carry blood, rich in oxygen and nutrients, to the baby and take waste products away.

After the baby is born, the cord is clamped and cut before the placenta is delivered.

An umbilical cord prolapse happens when the umbilical cord slips down in front of the baby after the waters have broken. The cord can then come through the open cervix (entrance of the womb). It usually happens during labour but can occur when the waters break before labour starts.

It is important to remember that:

- cord prolapse is uncommon, occurring in between 1 in 200 and 1 in 1000 births

- when it does happen, it usually occurs close to the end of pregnancy (after 37 weeks)

- a prolapsed cord is an emergency situation for the baby.

When the umbilical cord prolapses, it can be squeezed by the baby or the womb during a contraction. This can reduce the amount of blood flowing through the cord and so reduce the oxygen supply to the baby. The baby may need to be delivered immediately to prevent the lack of oxygen causing long-term harm or death of the baby.

It is not possible to predict a cord prolapse. An ultrasound scan does not show which women will have a cord prolapse, as the cord and the baby change position during the pregnancy.

When the baby is engaged (moves down into and completely fills the pelvis), the cord cannot usually prolapse. However, if the baby is not engaged, there is space for the cord to slip past and prolapse.

The chance of cord prolapse is higher if:

- your baby is not in the head-first position, particularly if the baby is breech (bottom first) or transverse (lying sideways)

- your waters break early or you go into labour prematurely

- you have more than one baby (such as twins or triplets)

- you have more water than usual surrounding your baby (polyhydramnios)

- you are having a small baby

- you have a low-lying placenta

- your waters are broken by a doctor or midwife (artificial rupture of membranes or ARM) when the baby’s head is higher up in your pelvis. Your doctor or midwife will usually only break your waters if the baby’s head is low down in your pelvis to try to avoid cord prolapse. If there is uncertainty, your doctor or midwife might break the waters in an operating theatre. If there is a cord prolapse, you would then be in the best place to have your baby quickly.

Your obstetrician or midwife will give you full information about your own situation if any of these conditions are suspected.

Umbilical cord prolapse cannot be prevented. However, if you are at increased risk, you may be advised to be admitted to hospital – then immediate action can be taken if your waters break or you go into labour.

Your doctor will discuss with you the option of being admitted to hospital from 37 weeks if your baby is lying in a transverse position or is changing position frequently (unstable lie). This is because you are more likely to go into labour after this time.

The signs of a cord prolapse are:

- you can feel something (the cord) in your vagina

- you can see the cord coming from your vagina

- your obstetrician or midwife can see or feel the cord in your vagina

- the baby’s heart rate slows (bradycardia) soon after your waters break. This can mean that the baby’s cord has been squeezed and the baby is not getting enough oxygen.

In some women there are no signs.

If you think you can feel the cord in your vagina or you can see the cord:

- phone 999 for an emergency ambulance immediately

- say that you are pregnant and you think you have a prolapsed umbilical cord

- do not attempt to push the cord back into your vagina

- do not eat or drink anything in case you need an operation.

To reduce the risk of the cord becoming compressed, you will be advised to get onto your knees with your elbows and hands on the floor, and then bend forward (as shown in the diagram below). You should remain in this position until the ambulance or midwife arrives.

The ambulance will take you to the nearest consultant-led maternity hospital or unit that can provide full care. In the ambulance it is safer for you to lie down on your side.

As your baby needs to be born as soon as possible, it is likely that you will be advised to have an emergency caesarean section but a vaginal birth may also be possible. Your doctor or midwife will explain the situation and what needs to be done.

A midwife or doctor may gently insert a hand in your vagina to lift the baby’s head to stop it squeezing the cord. Sometimes a tube (catheter) may be put into your bladder to fill it up with fluid. This will help to hold the baby’s head away from the cord and reduce pressure on the cord. You may be given oxygen through a mask and fluid from a drip.

Emergency caesarean section

If a vaginal birth is not possible quickly, you will be advised to have an emergency caesarean section.

You may need to have a general anaesthetic instead of a spinal or epidural anaesthetic for your caesarean section, so that the baby can be born quickly.

Vaginal birth

If your cervix is fully dilated, you may be able to have a normal birth or an assisted birth (forceps or ventouse) but only if this can happen quickly. A vaginal birth is less likely than a caesarean delivery when you have a cord prolapse.

A doctor or midwife trained in caring for newborn babies should be at the birth.

This situation can feel frightening for you and your partner but the midwives and doctors will explain what is going on. Every effort will be made to keep you fully informed.

For most babies, there is no long-term harm from cord prolapse.

However, even with the best care, some babies can suffer brain damage if there is a severe lack of oxygen (birth asphyxia). Rarely, a baby can die.

If your baby has come to harm, your baby’s doctor should provide you with full information about how this will affect him or her.

You should also be given information about support groups if you need them.

For most babies, the outcome is good. However, the experience can be frightening for you, your partner and your family. Talking to your midwife, obstetrician or GP about what happened can help.

It is important to remember that the chance of having a cord prolapse in your next pregnancy remains very low.

Further information

See RCOG patient information on:

If you are asked to make a choice, you may have lots of questions that you want to ask. You may also want to talk over your options with your family or friends. It can help to write a list of the questions you want answered and take it to your appointment.

Ask 3 Questions

To begin with, try to make sure you get the answers to 3 key questions, if you are asked to make a choice about your healthcare:

- What are my options?

- What are the pros and cons of each option for me?

- How do I get support to help me make a decision that is right for me?

*Ask 3 Questions is based on Shepherd et al. Three questions that patients can ask to improve the quality of information physicians give about treatment options: A cross-over trial. Patient Education and Counselling, 2011;84:379-85

Sources and acknowledgements

This information has been developed by the RCOG Patient Information Committee. It is based on the RCOG Green-top Clinical Guideline Umbilical Cord Prolapse (November 2014). The guideline contains a full list of the sources of evidence we have used.

This information was reviewed before publication by women attending clinics in Taunton, Milton Keynes and Durham, by the RCOG Women’s Network and by the RCOG Women’s Voices Involvement Panel.